How I Uncover d/Deaf and Disability History in the Archive

👋 Hi, I’m Emma O’Neill-Dietel! When I joined Rainbow History Project as a volunteer in February 2024, I had a question: Where are the d/Deaf and disabled people in D.C.’s LGBTQ+ history? Now I am a graduate student studying history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and I’m spending my summer in D.C. interning with RHP to answer that question. Join me for my blog post series “Behind the Scenes: Researching d/Deaf and Disabled LGBTQ+ History” over the summer as I dig into the archives and head out into the community to find answers!

As a deaf, queer, and disabled person, I have seen firsthand how many people in the LGBTQ+ community share these intersecting identities. My personal hypothesis for this overlap is that disabled people are already accustomed to living outside of society’s physical and psychological norms, which makes us more open to identifying and embracing our queerness.

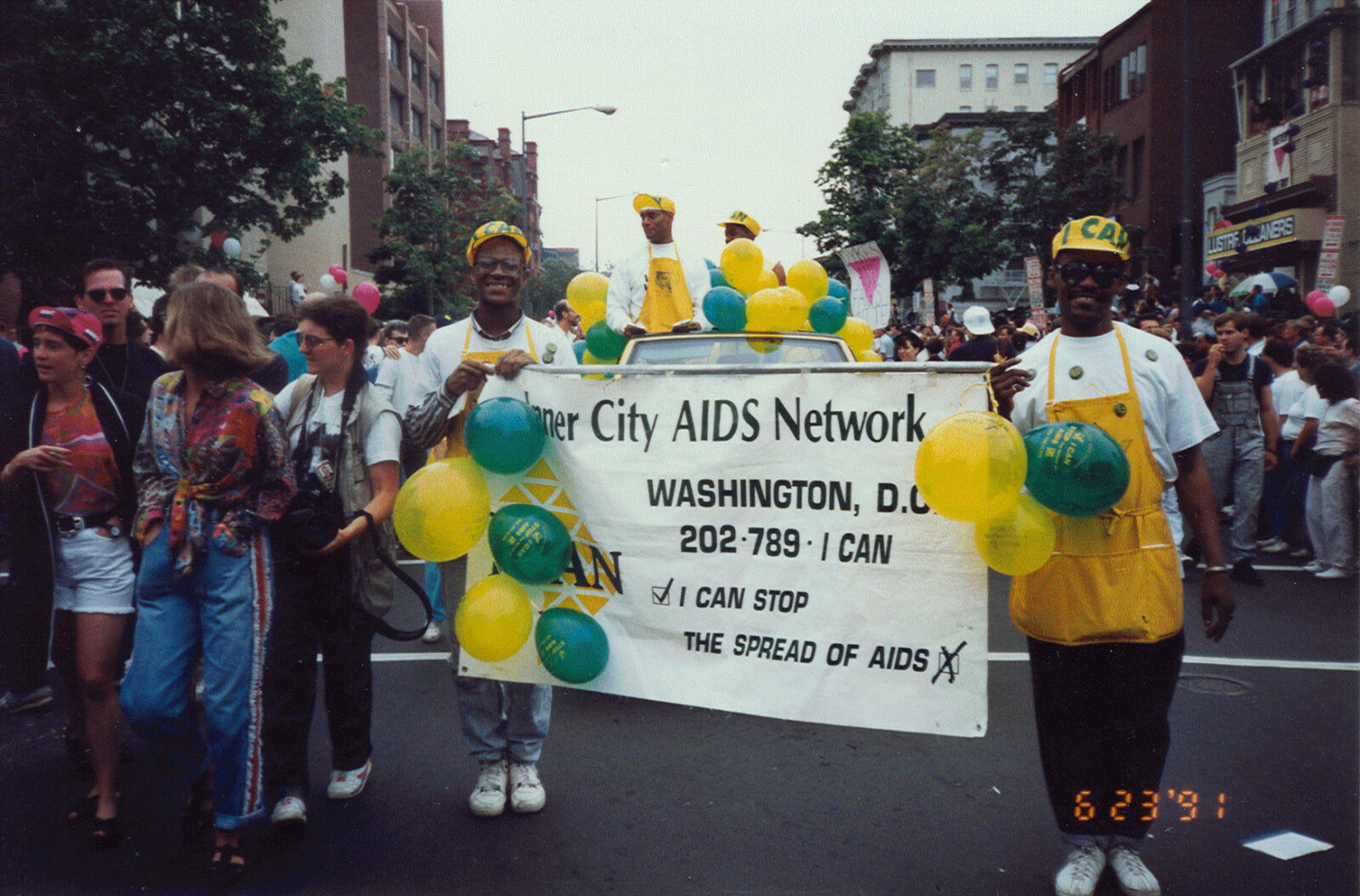

Two of the most well-known intersections between LGBTQ+ and disability history are the pathologization of homosexuality and the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In early 20th century D.C., queer people were institutionalized at St. Elizabeth’s hospital and subjected to electro-shock treatment. With the onslaught of AIDS in the 1980s, thousands of LGBTQ+ people became disabled. Many who survived became disability activists, advocating for legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act. But LGBTQ+ people in D.C. have been invested in community health, and by association, disability, since long before the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Whitman-Walker Health began as the Gay Men’s VD Clinic in 1973, and queer feminists have long been at the forefront of conversations around reproductive health. In all of these ways and more, disability and queerness have always been connected.

Not only do Deaf, disabled, and LGBTQ+ people share a common history, but these communities also present similar challenges to archival researchers. Like other marginalized groups, Deaf, disabled, and queer people are often underrepresented or mislabeled in archival collections. Our communities and the “professionals” who seek to define us cycle rapidly through changing terminology. (Pro tip, if you’re researching Deaf history by keyword searching newspaper databases, a search for “deaf” will usually turn up far more articles containing metaphors like “fell on deaf ears” than any actual information about Deaf people.)

Terminology used by archives to establish the metadata that makes archives searchable is often led by larger institutions like the Library of Congress. Queer and disabled archivists alike have identified changes in metadata that would better reflect those communities and help researchers search more effectively. (See Purdue University’s guide to critical disability studies and the University of Illinois’ toolkit of disability and accessibility subject headings.) That is what makes a community-based archive like RHP such a valuable resource: we archive LGBTQ+ history on our own terms.

A cursory glance at RHP’s finding aid and searches in RHP’s digital collection turn up few results for disability. However, because I already know the collection well, I have some ideas for where to start my research. To name a few, there are:

- The papers of prominent AIDS activists and educators like Earline Budd and Valerie Papaya Mann

- A collection of the Mautner Project, an organization created to support lesbians with cancer that grew into a resource for queer women’s health more broadly

- An unprocessed collection of photographs from members of the Capital Metro Rainbow Alliance, an organization of Deaf LGBTQ+ Washingtonians

- And of course, numerous materials about Whitman-Walker Health

Making disability visible in the archive is one thing, but making those archives accessible is another question altogether. For queer researchers, access might look like gender neutral restrooms in an archive. For disabled researchers, access might look like accurate transcripts for audiovisual materials, image descriptions of digitized photos, or physical access to the archive. As I continue on my research journey, I hope along the way to increase awareness of existing barriers, and maybe even help to remove them.

Stay tuned for regular blog posts documenting my research and collecting and sharing some of my findings. If you have a piece of LGBTQ+ d/Deaf or disability history to share, reach out to me at emma [at] rainbowhistory [dot] org.