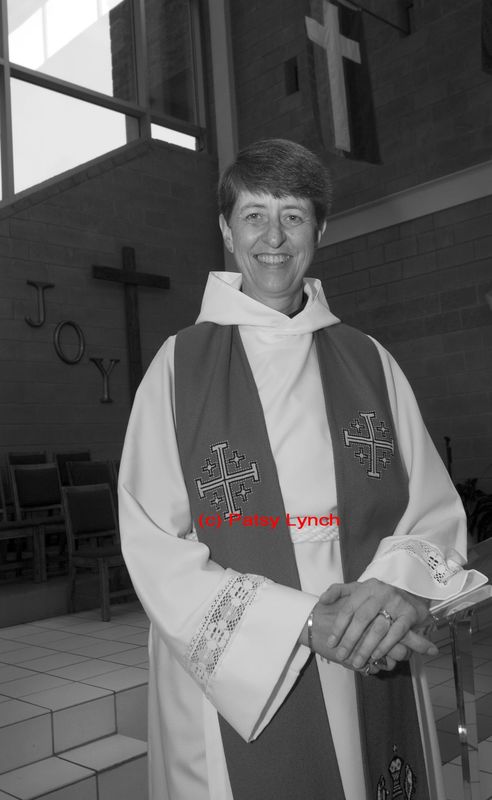

“My approach to ministry is more we’re all in this together,” lesbian pastor Rev. Dr. Candace Shultis said in an oral history interview with RHP. “We’re all in this together. We’re all equal in God’s sight. I didn’t come on staff just to minister to women. I came to minister to everyone.” Shultis, who served as senior pastor at the Metropolitan Community Church of Washington (MCC-DC), never anticipated being an ordained leader. She originally went to school for accounting and came to the nation’s capital as part of the US Marine Corps.

But what she brought to DC was far greater–a commitment to minister to Washington’s LGBTQ+ community during the AIDS epidemic. At a time when far-right conservative Christian groups argued that HIV/AIDS was a punishment for LGBTQ+ people and leveraged extremist Christian legislation against LGBTQ+ people’s rights and lives, Shultis held space for queer people of faith to worship, fight, and grieve together as numerous members of the MCC church died. Her story cements her legacy as a vital DC community pioneer, and other queer leaders of faith leading the charge during one of the LGBTQ+ community’s most difficult decades.

Rev. Dr. Candace Shultis grew up in Kingston, New York and Pittsfield, MA, earning her bachelor degree in accounting from the University of Massachusetts in 1973. After graduating, she moved to Washington, DC as part of the US Marine Corps. Shultis arrived in DC three years after the MCC-DC first came into being, then a group of LGBTQ+ people of faith meeting as the Community Church of Washington. The Church joined the Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches in 1971.

For three years, Shultis served as a disbursing officer in the US Marine Corps, managing financial records and overseeing payments using her undergraduate degree. Although Shultis did not attend MCC-DC until 1979, she felt called to religious ministry and left the Marine Corps in 1976 to attend the Wesley Theological Seminary. Then, she was working at Calvary Baptist Church, although she was a United Methodist.

She first learned about MCC-DC as part of the Downtown Cluster of Congregations meetings that she attended as a seminarian. Bob Johnson, Dan Schellhorn, and Ford Singletary attended on behalf of MCC-DC, and they lovingly said amongst themselves that she was one of them. She came out while still going through the ordination process in the United Methodist Church. At the time, MCC-DC met on Sunday afternoon, and Shultis recalled her first service.

“I showed up one day,” she said. “I cried through the whole service. I think when we find a place where our spirituality and our sexuality are both celebrated we tend to be overwhelmed at first. It’s good to always go back and remember those feelings. There are still people all over the world who need to know that God does not hate them but loves them completely and fully, just as they are.”

She earned her master’s of divinity by 1980 and that same year joined MCC-DC and was elected to the MCC-DC board, despite still serving at United Methodist churches in Hagerstown and Baltimore. Partially because of persistent homophobia within the United Methodist Church, Shultis wrote, “I realized where my heart and future ministry was and began the process of leaving the UMC. I turned in my ministerial credentials on April 1, 1983 which was also Good Friday.”

In a poetic moment, Shultis wrote, “on Easter Sunday, during the time of response following the sermon, I came forward, handed Rev. Larry Uhrig one of my stoles and asked him to keep it for me until I could take it on again as clergy in MCC.” By July 1983, she was ordained as a clergy within the MCC denomination and began work as an assistant pastor in August, during the height of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. She would transition to a full time pastor during Pastor Larry Uhrig’s sabbatical in 1985, and continued to work within the community for twelve years with Uhrig before he died from AIDS-related complications in 1993.

Uhrig led the late service on Christmas Eve and died early in the morning on December 28, 1993. His funeral was held on New Year’s Day, and Shultis lovingly remembers, “it was standing room only.”

Her and Uhrig’s leadership came during a critical time for the LGBTQ+ community. During a time when conservative pastors like Jerry Falwell called the AIDS epidemic “God’s punishment for the society that tolerates homosexuals,” and other far-right evangelical leaders pushed anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric during Reagan’s presidency, not unlike the rise of anti-LGBTQ+ religious leaders and legislation today, MCC-DC remained a key space where LGBTQ+ people of faith found community. Most importantly, the MCC-DC remained one of the few that even held funerals for people who had died of AIDS.

“We became kind of known as the place where you could come and we would do your funeral … it was just really hard on the congregation,” Shultis told the Washington Blade. In a testimonial on the MCC-DC website, Shultis explained that “we held too many, both for our church family and for many others who either had no family or whose families had disowned them. We also lost believed members who died of other causes,” including to suicide.

For Shultis, many queer saints passed through MCC-DC and remain tethered to the community and its welcoming buildings. The upstairs chapel was named after Robert and Wally Buchanan who left the money by which the land on which the present church stands was purchased. In fact, 415 M Street was the first property owned by any LGBTQ organization in Washington, DC, Shultis wrote. Bob Hager, a trustee and realtor, wrote the three contracts that facilitated this purchase and died while the MCC-DC was being built. His ashes were interred in the columbarium before the building was actually completed.

She still recalls Jim McCann’s funeral–one of the first funerals held for a church member who died of AIDS. McCann led the music ministry from the very first days of worship.

MCC-DC was not alone; faith played a multi-faceted role during the AIDS pandemic of the 1980s and early 1990s. While the Vatican released a letter in 1986 reinforcing their previous stance that homosexuality was a “defect” and Pope John Paul II reinforced the church’s ban on condoms to prevent the spread of AIDS, individuals and smaller communities within the Church fought for their survival as documented in Michael O’Loughlin’s Hidden Mercy. Other denominations witnessed similar schisms, but the MCC–as a church founded by and for LGBTQ+ people–remained devoted to caring for its community.

And outside of providing end-of-life care, Shultis remained a visible queer leader of faith in DC. As Larry Harris shared in a testimonial, he first learned about MCC-DC when he saw Rev. Shultis on television appearing on a talk show with other straight and gay clergy. Raised in strict Pentecostalism, he left the church because he was taught that homosexuality was a sin. He officially became a member of the MCC-DC right before Uhrig’s death and has been involved ever since, as a member of the board and Soundboard Ministry. As he wrote, “it felt good to know that God still loved me and accepted me as I am.”

By January 1995, Shultis was elected senior pastor and continued her ministry into the early 2000s, when she went back to school at Wesley Theological Seminary. She earned her Doctorate of Ministry in 2004. Her doctoral dissertation focused on documenting MCC-DC’s history, making her a vital collector of queer religious histories in the DMV area. She specifically focused in her research on intentionally creating more diverse congregations. While she shared with the Washington Blade in 2011 that in its earliest years, the MCC-DC served mostly white gay men, she urged Rev. Uhrig to prioritize the spiritual needs of women, especially women of color.

“You have got to pay more attention to women, more attention to people of color, the music had to change, the attitudes had to change … it took a lot of time to change the ratios but I think he really listened.” In the same Washington Blade article, Troy Perry–founder of the Metropolitan Community Church denomination–recognized that the Washington, DC congregation is “known widely for their gospel choir and they’ve sung at all our marches in Washington, DC.” Perry shared in 2011 that despite declining membership, MCC-DC remains one of the most active congregations within the MCC denomination.

In 2007, Shultis left MCC-DC to pastor an MCC church in St. Petersburg, Florida. She remained pastor at St. Petersburg, Florida’s King of Peace MCC until February 2021, serving temporarily at Resurrection MCC in Houston, Texas this past year. Like her steady leadership at MCC-DC, Shultis fought for attendees’ safety at King of Peace MCC, putting up security cameras after “MAGA” and swastikas were drawn in chalk on the pavement leading up to the church’s entrance in 2017.

Despite leaving the MCC-DC community in the 2000s, Shultis remains a key figure in its history and continued survival. MCC-DC remains the largest LGBTQ+ majority church in Washington, DC and one of the top 10 churches in terms of attendance numbers within the MCC fellowship in terms of weekly attendance–although attendance has waned in the last twenty years. MCC-DC serves one of the most queer communities in the country, as DC has the highest percentage of LGBTQ+ adults anywhere in the United States–14.5% of DC locals according to a 2024 Williams Institute report.

Shultis remains one of the key community pioneers of LGBTQ+ communities of faith in Washington, DC. As Mark Sprague, a former member of MCC-DC, wrote in response to her retirement, “you have been my pastor in DC and when you left – part of me left. After many prayers – God led me back to you in Florida – never planned it that way either. You have consistently taught me to believe in my prayers.”

Emma Cieslik is a volunteer at Rainbow History Project. Read Shultis’s profile as a Community Pioneer here.